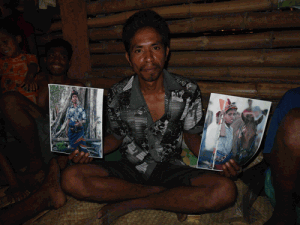

“Taking Tea with the Dead” — the working title of the book I’m not quite getting around to writing — was taken from an experience over 20 years ago, when I was invited in to meet the grandmother of some random villager in Sumba. I was a little put out, on being introduced to Granny, to find that she had died the day before. I picked this piece of exotica as my working title because I was pretty sure that I would find, revisiting these parts two decades later, that such esoteric traditions would have disappeared. Tea with the Dead would surely have died, swept out of Indonesia on a homogenising wave of modernisation. The title would reflect the changes in the country, and perhaps, in a self-centred sort of way, my nostalgia for something that was no more.

Not at all. When I went to visit my friend Mama Bobo the other day to arrange our outing to the pasola jousting, she was in a tizz. Her sister-in-law had died the night before. Now she had to scrape together weavings, pigs, buffalo and endless supplies of betel nut to contribute to the week of feasting that precedes the funeral. Of course I must come along (this would entail some scraping together of my own, for every guest must pay tribute). And so, 22 years after I first took tea with a dead Granny, I repeated the ritual. Which rather calls in to question that homogenising wave of modernisation. Though Granny slept through it, the remainder of her terrestrial existence was quite bloody. For the less squeamish readers there will be more, much more, in the book. Whatever it is called.