I’ve just spent a few days hunting whales in Lamalera, on the eastern end of Lembata island, off Flores. We didn’t have much luck, but last week, there was something of an end-of-season bonanza: in rickety wooden boats and using only long bamboo harpoons with rusty metal tips, the lads of Lamalera (and they are definitely Lads) brought in six whales. They get hacked up on the beach, which is littered still with spines and skulls.

|  |

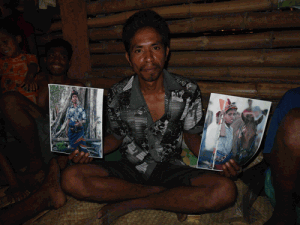

Every household gets its part: when I arrive the whole village is garlanded with shriveling flesh, dripping oil. It stinks. I hate to keep harking back to my past life, but when we were writing questionnaires for sex workers, the boys from Statistics Indonesia and I had long arguments about how to describe symptoms of chlamydia and other STIs in women. In the end we settled on this delicate formulation: a vaginal discharge “yang bau kurang sedap” (“that smells unfragrant”). Now I’ve got a new suggestion: “a vaginal discharge that smells like Lamalera”. The whole village exists in a miasma of stale fishiness; since dried whale meat is virtually the only protein on offer, that stuck-in-the-back-of-your-throat stench surfaces on the dinner table, too.

To punish me for my uncharitable thoughts, the whale Gods saw to it that the villager sitting next to me in the truck leaving Lamalera spilled a bottle of fish oil over my backpack. A little, portable miasma which at least creates space around me in overcrowded buses.

For readers in Britain, here’s a BBC feature on the whale-hunters of Lemalera: