For my 30th birthday, my mother framed school reports from the time I was 12 or 13. “Elizabeth is far too fond of the sound of her own voice” and “she sometimes sails too close to the wind for comfortable passage in the flotilla.” Are we really set in stone by the time we reach our teens?

I had cause to wonder this week, as I wandered West Sumba in search of people whose photos I had taken 20 years ago. One of my favourite pictures was of a young boy dressed up for the pasola jousting festival. He was too young to take part, but that didn’t stop him challenging the camera with a “you wait, I’ll show you” sneer.

Showing the pictures at a friend’s house, some one piped up: that’s Pelipus. That’s our Kepala Desa. The kepala desa, or village head, is now an elected position, arguably the one that has the most influence on people’s day to day lives in remote rural communities such as Gaura, where we were at the time. We went off to find Pelipus; he was preparing for the ceremony that marks the negotiation of a dowry. It starts with reading the entrails of a dog (provided by the bride’s side), to determine whether the partners are well-matched. The groom’s side is secretly hoping for bad omens, not necessarily because they want to see an unhappy marriage, but because a bad prognosis brings down the dowry. There’s no point holding out for too many buffalo if you’re going to have to return them when the couple divorces. Second order of business is to slaughter and roast a pig (also from the bride’s side); no serious bargaining can take place until everyone has eaten their fill. So Pelipus was busy, but not too busy to have a look at some old photos. The party oohed and aahed over pasola heros past and present. And then the village head found himself on my iPad.

He agreed to be photographed again, after he had wrapped himself into his party clothes. He told me that he had dropped out of school shortly after that first picture, and become a thief and a cattle rustler. It wasn’t until he got married and had a child that he saw the light and decided that the life of a local leader might be more palatable. (Delsi, a young Sumbanese friend who teaches high school, commented: “It’s a good strategy, to make the naughty ones head of the class. But it doesn’t always work.”)

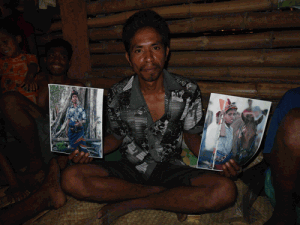

That “you wait, I’ll show you” look is still there, though when I bumped back along the 15 kms of unpaved road the next day to give him the prints of the “Then and Now” photos, he was looking a little the worse for wear — the dowry negotiations had continued until dawn. He and his companions had bargained a starting offer of 15 cattle up to 40 head of buffalo and horses. It would not surprise me one bit to come back in another 20 years and find that Pelipus is head of the West Sumba government.