We have moved to IndonesiaEtc.com

Please join us there…

It’s over two years since Portrait Indonesia went on the road. For several months now I’ve been rather quiet, hunched down over a computer, trying to pin Indonesia’s riotous diversity to the page. The book that will emerge in June 2014 will be called Indonesia Etc: Exploring the Improbable Nation. It will be published in the UK by Granta, in the US by WW Norton and in Indonesia by Godown, an imprint of always-inspiring Lontar.

The title Indonesia Etc is taken from Indonesia’s declaration of independence, which reads, in full:

We the People of Indonesia declare the independence of the Republic of Indonesia. The details of the transfer of power etc. will be worked out as soon as possible.

As Indonesia gears up for the 2014 elections, it is still working on its political “etc”. “Democracy by trial and error” was how one retired company head described it to me with a mirthless laugh. How far will decentralisation go? Will independent candidates and local parties be allowed? Much is still up for discussion or re-discussion. And yet the improbable nation muddles along remarkably well for such a young country. Re-reading Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address today, I was reminded that the United States, at a similar stage after its own declaration of independence, still had a bloody civil war ahead of it.

Though it looked touch-and-go for a few years at the start of this century, few people now expect Indonesia to face that kind of chaos in any of its vast territory (except, perhaps, Tanah Papua). In honour of Indonesia’s ongoing Etcs, and of my forthcoming books, this site is migrating to http://indonesiaetc.com.

- If you’re signed up to Portrait Indonesia by e-mail, you should now get notifications of new posts on Indonesia Etc.

- If you’re signed up by RSS feed, you’ll need to add http://indonesiaetc.com/feed/ to your reader of choice.

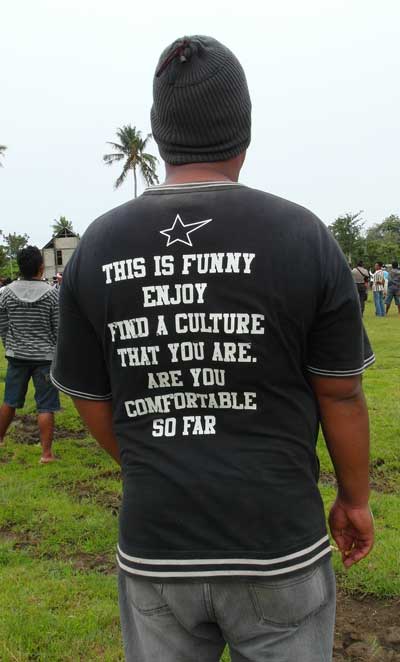

Thanks for sticking with the journey so far, and selamat jalan to the next incarnations.