In an average month, the world’s fourth most populous nation makes it in to the major newspaper of the world’s third most populous nation about three times. I know, because the New York Times has a very handy service that allows you to set up alerts; every time they run a story mentioning Indonesia, I get a heads up in my in-box.

I got one of those alerts today. “Buddhist-Muslim Tensions Spread as 8 Detainees Die in Indonesia”, the headline trumpeted. The Times is fond of stories about religious conflict, especially if they involve Moslems, so this wasn’t a huge surprise. But Buddhists? Really? I clicked on the link and found that the story was actually about a scrap between Burmese people who happen to be in a detention centre in Indonesia.

Now I know that Burma is flavour of the month just now (the expatriate bars of Bangkok have been rather folorn lately as the United Nations and NGO pack has moved wholesale to Yangon to try and get a piece of the newly democratic action). And I don’t doubt that the New York Times story, written in part by a former colleague of mine whom I respect very much, is right to muse about the possible spillover effects of violence involving the Rohingya. The story quotes a UN under secretary general saying that Buddhist-Muslim tensions needed to be controlled for regional security.

“All the governments are conscious that they can’t afford to let this kind of genie get out of the bottle,” he said. Indonesia, with the largest population of Muslims in the world, “is particularly sensitive about these implications.”

But is violence in Myanmar really what Indonesia’s security honchos should be thinking about right now? Let’s just looks at some of the things that have happened in Indonesia in the last week or two.

On March 23rd, 11 masked gunmen attacked a jail in central Java, killing four detainees and injuring two guards. On Thursday, the military admitted that the gunmen were special forces soldiers, taking revenge on common or garden thugs who had killed a colleague of theirs in a bar-room brawl. As if that wasn’t enough, the police fessed up that they had been warned of the attack in advance. Instead of trying to prevent it, they simply shifted the detainees to a less secure prison where they could be killed more easily. (On the good news side, both the police chief and the local military commander have been relieved of their duties as a result.)

On March 27th, a North Sumatra district police chief was bludgeoned to death while trying to arrest the owner of an illegal gambling den. Confronted with the police, the suspect’s wife had yelled that there were thieves in her house. As the Jakarta Post so delicately puts it:

In what is seen as a common practice in Indonesia, a crowd was attracted by the woman’s shouts and attacked the officers, assuming they were thieves.

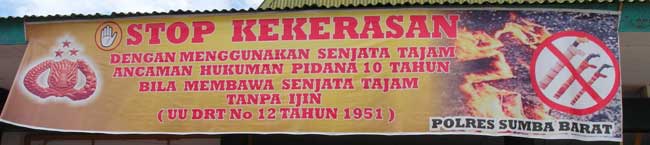

Indonesians are so fed up with the deeply corrupt police and the fetid court system that they routinely “main hakim sendiri” “play at being judges”. Most of the victims of mob justice are, as the Jakarta Post suggests, thieves, adulterers and other petty criminals, or just bad drivers. Too often, they end up dead, sometimes for stealing a duck or knocking down a pedestrian. Lately though, there has been a constellation of attacks against the police themselves. The Jakarta Globe helpfully lists a passel of assaults on police officers just in the last three months. They include:

Jan. 3: Three members of the Coordinating Minister for the Economy’s security force allegedly beat up a police officer when he tried to break up a scuffle between protesters and the guards outside of the ministry.

Jan. 29: Brig. Anthoni, a member of the Manado city police traffic unit, was beaten up after he tried to redirect a group of people during a funeral ceremony in an attempt to ease traffic congestion.

Jan. 31: Adj. Sr. Comr. Herman Sikumbang, the deputy head of the South Sulawesi police Brimob, was shot in the chest by a home-assembled rifle when he tried to mediate a clash between supporters of two different candidates during the South Sulawesi gubernatorial election in Makassar.

None of this has been reported by the New York Times. It seems to me that chronic distrust of law enforcement, a reflexive resort to mob violence including against the police, and the continued impunity of the armed forces are all far greater threats to security in “Indonesia, with the largest population of Muslims in the world” than a few Burmese acting out their hometown scraps in a detention centre overseas.