…takes a front seat in some of Indonesia’s smaller islands.

…takes a front seat in some of Indonesia’s smaller islands.

When Indonesians ask me what I find so special about their country, I often throw the question back at them. There’s usually much head-scratching and no clear answer. So then I ask: OK, what do you think defines Indonesia, then? Again, rarely a clear answer. The other day, though, a random unemployed guy I met on a boat came out with this: “Indonesia is a country based on the rule of law”. I nearly fell into the Banda sea (the deepest in the world, apparently). Indonesia is a country based on many things: the avarice of the Dutch, the populist nationalism of the founding fathers and the stubborn tenacity of the military are all candidates. But the rule of law would not appear in my top ten. Or even top ten thousand.

The rule of lawS perhaps, as in: one law for the rich and one for the poor. Benny made his surprising comment just around the time a court in Sulawesi was considering sentencing a 15 year-old to five years in prison for stealing a pair of sandals. It wasn’t smart of the kid to try and steal flip-flops from a policeman, but it probably wasn’t smart of the policeman to retaliate by beating the shit out of the kid, either. When his parents filed a complaint against the police for brutality the cops dragged the teenager in to court with the threat of a five year sentence. There was a bit of a national uproar; even normally judgmental religious leaders protested at the harshness of this prospective sentence. The press rushed to contrast the potential sentence with the lenient treatment of politicians and businesspeople accused of corruption. People convicted of stealing millions of dollars often spend just a few months in jails kitted out with gyms, spas and private dining rooms. In the end the kid was indeed convicted, but was sent home to lick his police-inflicted wounds with nothing more than stern warnings as punishment.

When Indonesians talking of siphoning millions out of the public purse they don’t call it theft, any more than Americans call their multi-squillion dollar lobbying industry “corruption”, though giving donations to politicians in return for legislation that profits your business smells a lot like corruption to me. In Indonesia, corruption is so deeply entrenched that it has it’s own set of time-saving initials: KKN (for Korupsi, Kolusi, Nepotism). And attempts to cut it off at the roots seem only to underline the hopelessness of the task. I read about one such in Kompas this week. “I’ll stop cheating when I know my stuff,” declared a 15 year-old middle-school student. This was considered a success of an anti-corruption programme which hopes to get schoolchildren to set themselves time-bound goals for going clean. The premise, apparently supported by survey data, is that all students cheat some of the time, and most of them cheat most of the time. Teachers do little about this because they are under severe pressure to produce “results” for the school (something that will sound familiar to anyone who teaches in an inner London school). Teachers in the wonderful Indonesia Mengajar programme, which sends graduates from the best universities to the most neglected parts of Indonesia to teach in primary schools for a year, say they feel the same pressure from a different source. “If I fail a student, the parents take it as an insult and just stop sending the kid to school” a teacher in the north of Tanimbar told me.

So cheating becomes a norm. And from cheating to lying, and from lying to not telling the whole truth about the distribution of funds, and from there to 100 th place on Transparency International’s list of least corrupt countries. In fact, Transparency International is one of the groups behind the programme to reduce cheating in schools. Its slogan: “Dare to be honest. That’s cool!” (“Berani jujur: hebat!“). Maybe it was just because I still had sea-legs after stepping off a 48-hour boat journey at dawn, but I was also pretty baffled by the large banner across the office of the harbour-master in Ternate (an island famed for perfidious double-crossing by greedy colonists and overbearing Sultans alike). The banner, which translates roughly as: “Don’t justify your habits, make a habit out of justice!” (Jangan benarkan yang biasa, biasakan yang benar!) is apparently a rallying cry for honesty in the workplace.

It seems to me it’s a long road between those sorts of slogans and a country based on the rule of law.

I welcomed 2012 while in the Banda islands, moderately famous because just one of the nine tiny islands of this isolated group was once thought to be a fair exchange for Manhattan, something I wrote about while a Reuters correspondent in these parts two decades ago. The differing fortunes of the two islands — the one still rich in nutmeg, the other now just plain rich — inspired Michael Schuman to give us this homily of protest at protectionism. He makes a sensible enough point; economies need to anticipate tomorrow’s needs rather than try to entrench today’s. Could the Dutch have anticipated that the perfidious Brits would smuggle nutmeg over to the similarly volcanic, sea-side location of Grenada and break the Dutch monopoly over the spice trade that way? Probably, yes. Could they have anticipated that the market for nutmeg would implode in large part because people got better at preserving ice and chilling food, and thus had less need for preservatives such as nutmeg? Maybe. Did they give a damn about the long-term prospects of the crop, or indeed the local population? The answer to the second part of the question is obvious: since the Dutch slaughtered most of the indigenous population in order to establish the monopoly, they were unlikely to be overly concerned with the continuing welfare of the slaves they imported to work the nutmeg plantations. Whether they cared about the price of nutmeg in the long term is harder to guess at. Nutmeg provided a nice little bonanza for a while, but it was the vast sugar plantations of Java and rubber plantations of Sumatra that underwrote most of the development of the Netherlands, now one of the world’s more generous welfare states. Though by Michael Schuman’s standards the nutmeg growing islands of Indonesia are poor, it’s perhaps worth noting that, with the crop requiring virtually no work and nutmeg now fetching US$12.00 a kilo and the mace that covers it US$ 27.00 a kilo, the nutmeg planters of Banda are the envy of many people on other small, far-flung islands in Indonesia.

I was interested to find a staunch defender of the Dutch in the form of the British naturalist Alfred Wallace — some say the true originator of Charles Darwin’s theories of evolution. Wallace spent 12 years wandering this part of the world killing things: shooting birds and pinning down butterflies mostly, though he did a fair bit of damage to the orang-utan species, too. Writing in the 1850s, long after the Brits were growing nutmeg elsewhere, he claims that the Dutch had a moral duty not only to monopolise nutmeg, but to destroy any excess trees that might raise production and lower the price. His logic is as follows: nutmeg is not a necessary commodity. It is not even used by the natives as a spice. (That’s still more or less true, though they do make some quite good jam out of the fruit that surrounds the nut). So raising the price does not hurt the local population. On the contrary, pushing up the price and putting the gains into state coffers provides a source of income for the state that would otherwise be raised from the local population in taxation. And we all know that taxes do hurt.

It would be a fair argument if the gains did indeed go into state coffers, and if they were indeed used to benefit the people who were doing the picking, peeling, drying, and shelling of nutmeg. If money made from the (admittedly not very onerous) sweat of the Banda islands is used to swell private purses or subsidise the already relatively well-sated needs of people in the Netherlands, on the other hand, or even of people in Java, it’s harder to make the case. It’s a debate which is still immensely relevant today, as Indonesia struggles to divvy up the wealth that geography has distributed so unevenly across its great surface. Of which a great deal more anon…

For the last few weeks, I’ve been in Maluku, formerly known as the Moluccas, famous for spices and inter-religious carnage. The hideous religious riots of 1999-2002 have left a deep scar on this part of the country. Whole communities were uprooted and there was a shift between islands as people who formerly lived perfectly happily with neighbours of another faith consolidated into single-faith blocks.

Needless to say, this makes me furious. I have never understood how people can grow to hate someone else because of who they choose to pray to, any more than I can understand hatred based on who people choose to sleep with. In the spirit of conciliation, therefore, I’m posting evidence that all religions in Maluku are equally adept at really kitsch religious art.

The Moslems in Banda Neira give us these Id-ul-Fitri wishes, complete with Arab style mosque and a Reggae Che Guevarra.

At the Chinese cemetery, also in Banda Neira, we have a breastfeeding lion standing guard over the graves.

Further south in Saumlaki, in the Tanombar islands, virtually every house has some icon or other to offer to the competition. This Jesus Sneezed fresco caught my eye.

I am sad to say that the Protestants have done less to defend their title to kitsch, and I have little to offer on that score. At the risk of being accused of bias, I do think Maluku’s Catholics have made a more than adequate contribution that perhaps makes up for the slackness of the other Christians. This larger-than-lifesized statue commemorating the first Catholic baptisms of head-hunting “savages” in Tanimbar takes some beating.

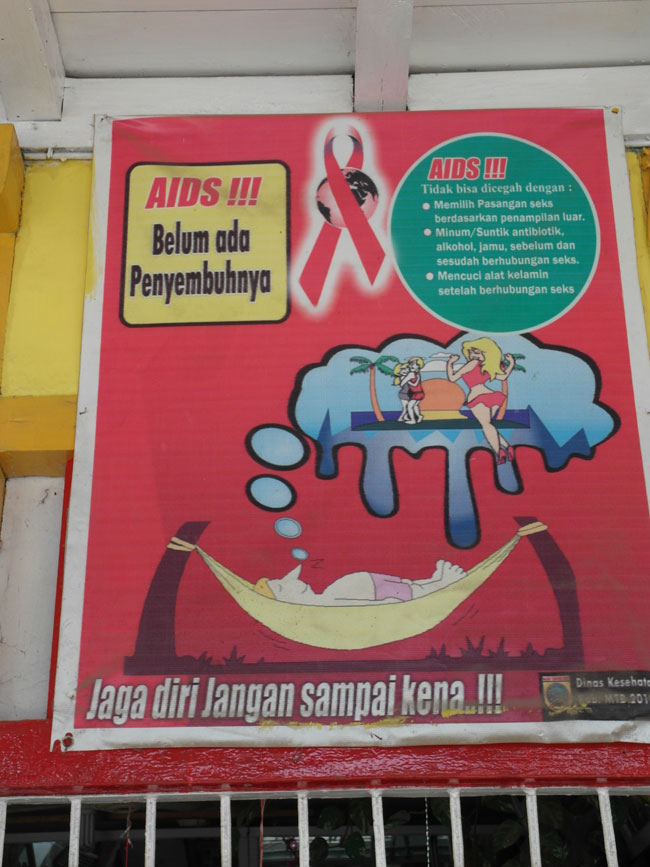

I have a collection of daft AIDS posters going back years, but I’m glad to say they are getting harder to find. This one, in Saumlaki, the main town in the remote Tanimbar islands, was thus a great find. The headline reads: AIDS: there’s not yet any cure! On the right is this helpful information:

AIDS!!!

You can’t avoid it by:

Some, including the South African president Thabo Mbeki Jacob Zuma* and uber-philanthropist Bill Gates would take issue with the last point. I, of course, would take partial issue with the second — you can avoid AIDS by taking medicine, you just can’t avoid HIV that way. But the most egregious part of this ad is the illustration.The population of Tanimbar is largely Melanesian. Overwhelmingly the highest HIV risk for them is the sex they might have on their frequent money-spinning travels to neighbouring Papua. Indonesian Papau, rich in minerals, forests and much else, is swimming in cash. It is also swimming in HIV; it’s epidemic looks more like East Africa 15 years ago than it does like any other part of Indonesia today. And it is populated not by pointy-nosed tourists with straight blonde hair but with flat-nosed Papuans with crinkly black hair.

Most AIDS posters are pretty useless, in my opinion. But this poster associates HIV with Western tourists slow-dancing under the palm trees — an “other” that most people here will never come across, while saying nothing about commercial sex in high risk areas (Papua, but also with the local transgender (or waria) population). Those are very real risks that many certainly do face, at least if Astuti, one of the latter, is to be believed. She excused herself early from a grilled fish dinner because her phone rang. Not her Blackberry, that’s for friends and family, but her “HP selinkungan” (cheating phone). In Tanimbar from neighbouring Kei for around a year, she hasn’t had a day without clients. And though she has helped distribute condoms and promote testing in other cities around Indonesia (in some of which one transgender sex worker in three is infected with HIV), she’s seen no sign of an HIV prevention programme in Tanimbar. By maintaining the fiction that something is being done about HIV prevention in Tanimbar, this poster is a lot worse than useless. It is actively dangerous.

*(Thanks to Thakhani for correcting my presidential confusion.)

Indonesia starts the new year hopefully: it has been upgraded to investment status by one of the rating agencies. It’s no huge surprise; rating agencies tend to think quite short term, and short term, the indicators look good. The Financial Times is enthusiastic about what it calls a “demographic dividend” i.e. lots of young people. “Indonesia’s dependency ratio of workers to retirees is dropping from about 55 percent now to 45 per cent by 2025,” says the pink paper. What looks to the FT like “favourable demographics” looks to me like a collapsed family planning programme that will surely be problematic in the longer term.

But the paper’s David Pilling sees three other sorts of trouble: infrastructure, infrastructure and infrastructure. To that I would add pandemic corruption and the gaping absence of an independent judiciary, but I can’t disagree with the observation that there has been an underinvestment in ports and power stations. This little video was shot off a cargo boat “docked” at Lirang in Southwestern Maluku, at the sea border with East Timor (the grey land mass in the background of some of the shots is East Timor — a hazard for the users of cell phones because their powerful comms get passing boat passengers so excited about having a signal that we don’t clock that we’re paying international roaming charges). The scramble to get on board is a pretty good illustration of what many people on the remoter islands deal with if they want to go anywhere else, but since goods have to be offloaded in the opposite direction it also shows why petrol sells at more than five times the government-set subsidised price, and why it is so difficult to build up the other sorts of services that people want.

I’d agree, too, that more power stations are needed. I’ve learned that one of the easiest ways to judge the level of “development” of a town is to ask whether it has electricity 24 hours a day. Even when the answer is yes — and in this part of Indonesia it rarely is, below the sub-district (kecamatan) centre level — brown-outs are a norm; the sound of generators is almost as common in the evenings as the buzzing of mosquitos. I’m in two minds, however, about the underinvestment in roads. Building roads is the most palpable and most immediately achievable way for a newly-elected Bupati, the district heads who in this era of regional autonomy wield an immense amount of power, to show that he is delivering “development”. Building roads has lots of other advantages too. It’s an easy way to repay the favours provided by Chinese Indonesian businessmen (most of whom at least dabble in contracting) during the election campaign, not least because road building is easy to dole out: this 5 km stretch for PT Putra Wijaya, that 12 km block for the more generous PT Sinar Jaya. It involves contracting and buying stuff, so the possibility for kickbacks and skimming cash off budgets through overpricing is manifold. And it is endlessly repeatable. I’ve tortured my rented motorbikes over roads that are beginning to crack and subside at the beginning of the newly tarmacked stretch when the trucks are still out dumping asphalt at the far end of the same stretch, just a few kilometers down the road. They may as well have taken a can of black spray-paint to the existing

earth track.

In this age of transparency there’s often a “Papan Proyek”, a project information board, at the site of a new road construction project, so it’s possible to know what the formal budget is. If you added up all the stretches of road under construction in Indonesia, you’d probably get to a respectable sum. The problem is not an underinvestment in roads on paper, it is an underinvestment in well-engineered, sustainable roads in practice.

While Indonesia’s Christian churches do their best to get people excited about Christmas, the pine tree iconography has a hard time competing with the palm tree reality. Local Christmas trees are mostly made of hoops of ugly white tinsel, like the tattered hooped skirt of some antebellum Cinderella. I did, however, like this variant made of discarded water bottles which I found in Kisar, in Maluku. Quite by chance, whiling away the night on a dock on another island with a little rant about litter, I commented on this inspired use of rubbish. It turned out that Bpk Elis, who I was talking to, was the designer of the very tree I was describing.

Though I’m in the most stoutly Christian part of Indonesia, the frenzy of consumerism is mercifully muted. This was certainly true in the village of Ohoiwait in the Kei islands where I spent Christmas with no electricity or phone signal, no gift-giving, but some desperate showing off of frilly new dresses at the three church services I went to in two days. In villages like Ohoiwait kids are used to making their fun from whatever is at hand. Tyres whipped along with sticks are still popular among boys, and spinning tops provide hours of competitive fun. But for sheer something-out-of-nothing genius, this helicopter sort of thing, made from a hollowed out mango stone, a whittled stick and a piece of string, which I found in a three-house hamlet in West Sumba, surely rates right up there.

I’ve just spent five days (and five nights) on the deck of a cargo ship travelling between Wini, in West Timor, and the Tanimbar Islands in southern Maluku. As in any five day period, there are good moments and bad. The bad would certainly include the hours when the lads sitting close to me, having been drinking palm wine for several hours, broke out a guitar held together with duct tape and took on the booming karaoke machine, a competitive cacophony of tuneless shrieking. The good would include the early evening hours, when the sun had cooled enough to sit dangling one’s legs over the prow (which is also as far as it is possible to get from the relentless karaoke machine), staring at the rippling sea and beginning, gradually, to get a sense of the enormity, perhaps the impossibility, of Indonesia. The very best moments come when those evening hours are punctuated by dolphins, who have come out to play with the passing ship. After a bit, the sky goes fiery, then dark. On truly exceptional days, a blood-red moon rises out of the depths, paling as it climbs, showering gold across the sea. Drunken singing seems like a small price to pay.

|  |

I’m always happy to see the Boys in Brown (in Indonesia that’s the police) supporting a good cause. Right now, they’ve decided to take on what I think is the biggest blight on this gloriously haphazard nation. Not corruption (that would be a stretch for the police), not a bloated and ineffectual civil service (ditto), but litter. Indonesians have gone from wrapping food in banana leaves to dressing food, drink, shampoo, sweets, virtually everything in shiny plastic wrappers. The national obsession with buying things in tiny quantities — just enough hair gel to achieve the Bus Station Lout look for a single spiky Saturday night — means there is an awful lot of wrapping around. And all of it gets discarded on the spot, as soon as its contents have been consumed.

Out the bus window, onto the floor of the airplane, over the side of the ferry into the sea — the possibilities for littering are endless, and all enthusiastically embraced. On an otherwise gorgeous and totally deserted beach in East Sumba a couple of weeks ago I counted 57 discarded plastic drinks containers in the shade of a single tree. A big tree, but still. At sea, those people who obey the “Keep this Ship Clean” signs and dutifully put their empty drink can in a bin can be forgiven for wondering why they bother — when the bins are full, a staff member will himself dump their contents over the side of the ship into the sea. Comments about this behaviour draw only blank looks: what behaviour?

So I’m thrilled that the police have nice new banners trashing litter. “Let’s work together to support and carry out the CLEAN INDONSIA MOVEMENT!” It would be more convincing, perhaps, if the police had spent as much time clearing up the garbage in their own yard as they did putting up the banner.