It’s local election season in many areas of Indonesia. That means posters of well-fed used car salesmen promising vaguely to fight corruption and enrich the “rakyat”, the majority of Indonesians who live from day to day or month to month. It also means that towns and villages are filled with “Tim Sukses” — swarms of volunteers who try to get the vote out for their candidate, often with the help of envelopes of cash.

Here’s my question: why does money politics work? I put the question in a slightly more direct form to someone in Aceh who was cross because she’d been offered only 100,000 rupiah — less than US$ 11 — for her vote. “I got that in 2006, and there are more candidates this time, all of them making offers. Why would I give away my vote for just 100,000?” Why, I asked her, didn’t she just take 100,000 from all of the candidates, and then vote the way she would have voted anyway? She looked shocked. “If I’ve promised my vote, I have to deliver my vote!” In other words, money politics works because enough people are honest in their corruption.

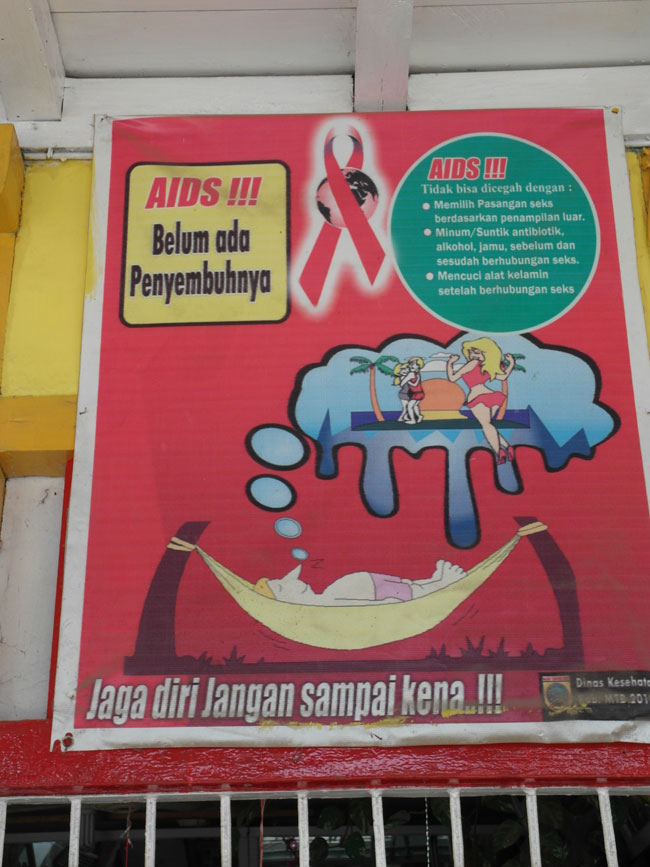

As this poster from the election oversight commission in the East Aceh town of Langsa suggests, the vast spending on campaigns, including vote-buying, leads to a cycle of corruption. Elected leaders resort to graft just to get back the cash they’ve spent. Sometimes, the payback is in contracts, not cash. But every which way, it means public money is badly spent. This report from the World Bank gives a pretty clear picture of how it all works. It refers to the last round of elections in Aceh, the rich Westernmost province of Indonesia that teeters perpetually on the brink of independence, but — pace the separatists — there’s virtually nothing in it that is not just as true of the rest of Indonesia.

The exception is wrapped up in the final point about voter behaviour: intimidation. In Aceh, people are talking about “Terror Politics” as well as “Money Politics”. Last week I made a giant leap from the tuna fishing grounds by the Philippine border to the far West of Indonesia to witness the local election campaign in Aceh. I didn’t see it because the elections have been postponed for the third time, in part because the fractious former separatists, unhappy with the current governor who is also a former separatist, have been obliquely threatening unrest if Jakarta doesn’t roll over and do everything it can to undermine the incumbent. I can’t say that it is their camp, Partai Aceh, that was behind the drive-by shooting at the house of the Governor’s Tim Sukses head last week. But party activists in the local coffee shop were not denying it when I reflected that a postponed election increased their chances of getting “their man” — a crusty old soul who has spent much of his adult life in exile in Sweden — elected. If this all sounds complicated, it is (there’s a good run-down of the issues from the International Crisis Group and more in Inside Indonesia).

According to a former candidate for mayor in Langsa, home to the anti-money politics poster pictures above, terror Politics is the order of the day, at least in rural areas. “If you stay in a village for a week before the elections, I guarantee you’ll get a knock on the door in the middle of the night.” In an area where a knock on the door at night meant near certain death for over 15 years, either at the hands of a shadowy group of thugs and rebels who eventually gelled into Partai Aceh, or at the hands of the Indonesian army that fought to suppress them, it’s pretty persuasive. Even more persuasive, perhaps, than 100,000 rupiah.