So Indonesia is going to require expatriate lawyers to take an ethics test, in Indonesian. I think this is a splendid idea; though they are not actually allowed to practice law in Indonesia, foreigners certainly have a lot to learn from Indonesian lawyers when it comes to ethics. Here’s some essential vocab to get them started:

Suap

“Salary supplementation”. It literally means “to spoonfeed” and some cynics translate it as “bribe”, but they haven’t studied legal ethics in Indonesia.

Cuci uang

To “wash money”. Indonesians are very concerned with personal hygiene. Many Indonesian lawyers feel they have an ethical obligation to ensure that money stays clean.

Itu biasa

“Tax compliance” This is best understood through a recent quote from a lawyer explaining why the head of the Constitutional Court registered his Mercedes in the name of his driver. “Itu biasa, dalam satu orang namanya ada pajak progresif, dia coba untuk pakai nama orang lain. Ya itu kan biasa, Indonesia itu kan semua ini begitu kan.” A literal translation for people not familiar with Indonesian legal ethics would be: “That’s normal, if a person is subject to progressive taxes, it’s normal that they would try and use someone else’s name. In Indonesia, it’s all like that, right?”

Koper

“Bank account”. Derived from the word for “suitcase”, this word describes the mechanism through which most Indonesian lawyers get paid.

Asing

In common usage, this means foreign. To the Indonesian legal establishment, however, it means “Guilty”

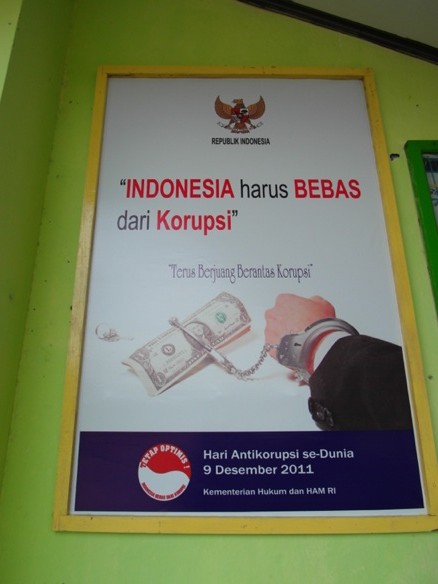

KKN

A contraction for Korupsi, Kolusi, Nepotisme, this translates as “Business as Usual”

In the interests of enriching the ethical understanding of foreign lawyers in Indonesia, I offer the Golden Loophole Award for the best additions to this list.